Festival de Almada 2025: Miguel Martins interview

Forty years on. A view across four decades of the Festival de Almada with one of its founders and stalwarts.

Jeremy Malies

July 2025

Miguel Martins heads up communications and has been at every festival since the 1984 inception in various capacities. He can justly see himself as a shaper and leading light of the festival but for this interview he simply reminisces. Martins is a versatile man of the theatre who has combined a career as an actor with being a publicist in the arts field.

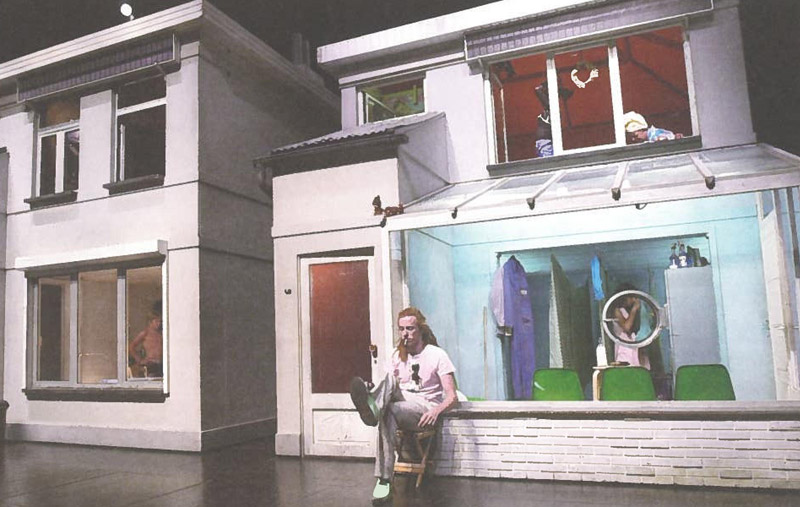

O baile, encenação de Hélder Costa para A Barraca. 1989.

Photo courtesy of Festival de Almada.

Miguel tells me that he has been here from the word go, and as a young actor worked in collaboration with the Almada Theatre Company. The obvious question is what he sees as having been the catalyst. What was happening in 1984 that kindled the fire for all this?

Miguel immediately mentions the Carnation Revolution of ten years earlier, the overthrow of the authoritarian Estado Novo government in April 1974. This was in part by junior army officers, some of whom were left-leaning. All of the people seeking to overthrow the government wanted to end colonial wars and “put an end to the state we have reached”, to quote Salgueiro Maia, one of the heroic captains of the Revolution.

Ripple effects over the next ten years included a process of cultural decentralization whereby artistic efforts moved from the metropolis right across the country, with the significant work happening among semi-professional groups and often seeing young people taking a lead.

Miguel is 59 and came to Almada at the age of nine when his parents bought a house here. He is the son of an electrical engineer who was an army captain at the time of the Revolution. His father participated in the “movement of captains” that would overthrow the fascist regime and pave the way for democracy.

Miguel is self-effacing but finally has me understand that he was among the pioneers of the festival, and as a young actor he worked with a group that collaborated with the Almada Theatre Company.

The conversation returns frequently to theatre critic and drama director Joaquim Benite whose company settled in Almada in 1978. Miguel met Benite in Almada at a café called “Calhambeque” which they both frequented. Miguel was 16 or 17 years old at the time. He didn’t realise straight away that theatre would be the path he would take and describes how this course unfolded over time. He joined the Almada Theatre Company and its cast permanently in 1990 having started collaborating with them in 1983 and appearing in a few shows in the meantime. He says, “I had already been on a youth television programme called Peço a palavra in 1977, this being directed by the great Portuguese actor Mário Viegas. I went to a casting session and was chosen, and had also participated in some amateur productions.”

Miguel and I are on the forecourt of the theatre here that bears Benite’s name in recognition of his broad transformative work that has seen Almada become a cultural hub not just across Iberia and Europe but worldwide. Another versatile man, Benite had a career as a news journalist before becoming a theatre critic, having been editor-in-chief of several national newspapers. The theatre’s minimalist poured-concrete lines define the area in which we are sitting.

Todos Indios by Ballets C. de la B. in 2001.

Photo courtesy of Festival de Almada.

Miguel says, “Benite was the creator and lynchpin of all this. But at the start, drama developed from the ground up in Almada with theatre-makers going out to colleges to mentor young people.” His vocabulary at this point suggests that the shows being created were small-scale with an accent on spontaneity. He continues, “Often the youngsters we encountered in the early days had shows that were close to a level where they could be presented more or less immediately.”

Joaquim Benite was the creator and lynchpin of all this.” Miguel Martins on Joaquim Benite.

The recollections here sound like the early (immediately after World War Two) projects at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe until that undertaking lost its soul to major corporates. Miguel reminisces about how spectators at the early festivals in the old (Beco dos Tanoeiros) area of Almada would bring their own chair or plead for one from coffee shops. Apartment owners would offer their homes as changing rooms while actors readied themselves for the improvised open-air stage. Miguel describes the evolution of the festival as being a long road but one in which additional paths have opened up. He says that often the conceptual leap is the realization that you need to go down these new paths.

Festival director, Rodrigo Francisco.

Photo credit: Pedro Castanheira.

I ask Miguel if he can trace a developmental pattern in the shows that have been presented since 1984. “Pattern? Perhaps not. But what I did see was Joaquim Benite consistently seeking out companies who were the best of their kind within the different types of theatre. And there was one thing that Benite didn’t like. He didn’t want creative people to toe the line and would not trust those who did!”

Miguel continues, “By 1986 the festival was beginning to externalize, and one of our first visiting companies from another country was a Spanish street theatre group. We’ve always been media-friendly, and the press have warmed to us in print and photojournalism. Somehow, we’ve managed to keep in the news!” Miguel attributes this in part to sheer popular appeal. For the first two years there was a jury of theatre critics but from 1988 it has been theatre-goers themselves who have been polled on what is the year’s best show. It’s an aspect that has meant more column inches for the festival.

Exhibition of prominent previous shows.

Photo credit: Pedro Castanheira.

The significance of the summer of 1989 elsewhere in Europe is hardly lost on Miguel, and he mentions that when the Polish company Maya Theatre under Kazimierz Grochmalski visited in that year the audiences in Almada felt connected to political upheaval in the Communist bloc even if Grochmalski’s work was not markedly political.

Miguel is of course too diplomatic to even hint at what has been his favourite show across so many iterations of the festival since 1984. I prod repeatedly and finally draw him on something that was memorable, Carlo Gozzi’s play The Love for Three Oranges in 2003. It was brought here by the Swiss Brechtian director Benno Besson. Miguel was one of many amazed spectators. He tells me how he was struck by the simplicity and severity of the scenography. In 2004, Joaquim Benite staged The Showman by Thomas Bernhard and Miguel played juvenile lead Ferrucio depicting the character with his arm in a cast throughout. Bernhard is perhaps the contemporary playwright that Miguel admires the most.

Photo credit: Pedro Castanheira.

What advice would Miguel give to young people who want to go into acting? I don’t think the phrase exists in Portuguese but in the mixture of languages through which we are flitting, I think Miguel comes close to the aphorism that free advice is worth exactly what it costs. “Do what you feel propelled to do in life, and if you have a good idea for theatre then it’s your duty to make it happen somehow.”

He sees the theatre-makers in the early years of the Almada festival as shipmates who were all mucking in. It didn’t matter who had the most impressive degree in theatre studies, if it made sense on a particular day for you to sweep the stage or serve the drinks then that is what you did. Three decades, on it’s very different. He regards one thing as a sacred duty – transmitting enthusiasm for the theatre to children at schools and colleges.

I’ve just watched The Tempest which brings us on to Portugal’s national poet, Luís Vaz de Camões, who was (just about) a contemporary of Shakespeare, dying in 1579 at the age of 55 when Shakespeare was 15. Miguel recalls a visit by actor and literary scholar António Fonseca as part of a community project at the Almada Municipal Theatre, now called the Joaquim Benite Municipal Theatre. Fonseca is a further education lecturer in Coimbra and known for reciting Camões’s Homeric epic Os Lusíadas either solo or in groups. Miguel contributed a few lines to the recitation.

Miguel gives me an introduction to Camões’s decasyllabic octaves, tapping out the rhythm with the kind of relish and precision that Peter Hall would use when lecturing on Shakespeare’s meter. His “AB AB AB CC” sends tremors down a trestle table at which we are sitting outside the theatre. Records are sketchy (imprecise by a year or so) but this is probably the five hundredth anniversary of Camões’s birth, and it is being celebrated widely.

Photo credit: Pedro Castanheira.

The lecture in verse structure over, Miguel gives me his verdict. “The verse is very difficult to recite but when done with any kind of skill it falls beautifully on the ear.” Miguel was pleased to have contributed to Fonseca’s treatment of all ten cantos.

Looking through production photos from previous festivals we fall to discussing Samuel Beckett. Miguel is a Beckett fiend and particularly fond of Happy Days. I say that I’m fresh from seeing an underwhelming production of it in Hackney, east London. The production images suggest that there was nothing underwhelming about the production here in 2006 by Giorgio Strehler and starring Giulia Lazzarini as Winnie. I try to lecture Miguel with my idea that Winnie’s rubbish dump is nuclear fallout. He is more circumspect and says we should not be prescriptive about meaning. He then offers to introduce me to Lazzarini who he believes is in the audience tonight. We wait for her to walk by but are disappointed.

Giulia Lazzarini as Winnie in Happy Days.

Photo courtesy of Festival de Almada.

Miguel’s lens switches to wide-angle. “The shows here are different perspectives on the world from companies with different ideas, attitudes, ways of seeing and recommendations for us.” He notes that from 2001 onwards there have been many instances of productions created at the Almada Festival being transferred to other major venues including, perhaps inevitably, Lisbon. This was a steppingstone by which the Almada Festival put itself on the world theatrical map and can make a claim to being the drama capital of Portugal.

Miguel sees the group endeavour here as a paddle steamer and he sketches one for me. This is a little obscure. It takes us a while to get to the bottom of his figurative language. The propulsion (rather than engine) at the Almada Festival is the hundreds of people inhabiting the paddles and putting their shoulders to the wheel to make this arts festival into the maritime equivalent of an ocean-going liner. It’s a seductive analogy from an engaging man.

This interview was conducted in a medley of languages but with significant Portuguese-to-English assistance from Marta Prieto.