“Far Away” and “A Number”: Caryl Churchill

Neil Dowden on two Caryl Churchill plays

1 March 2020

During six decades as a playwright, Caryl Churchill has not only continually innovated with form but also tackled an extraordinarily wide variety of subjects. She never repeats herself. The one constant is her intent to challenge audiences to look outside their preconceptions and, often, to step outside of their comfort zone. ln recent years (like Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter in their late careers) Churchill’s work has become more pared down and concise, while still making a substantial dramatic impact. By happy coincidence, two short prescient dystopian dramas she wrote in the early 2000s have been staged at the same time in two London theatres: Far Away (2000) at the Donmar Warehouse and A Number (2002) at the Bridge Theatre. Though they both feature disturbing depictions of the future, they deal with different aspects and are quite different in approach, so make a fascinating comparison.

Despite being only 40 minutes long, in three brief scenes Far Away manages to create a portentous vision of disaster on a global scale. In a cottage “far away” in the country, a young girl (Joan) is woken up in the middle of the night by a startling noise. Her aunt (Harper) says it must have been an owl shrieking. But Joan knows it was a human scream because she has climbed down the tree outside her bedroom window and seen her uncle hitting adults and children with a metal stick as he forces them into the shed. After trying to divert her with various lies, Harper tells her, “You’ve found out something secret … Something you shouldn’t know … Something you must never talk about ..” The scene works brilliantly because it subverts the scenario of a responsible adult consoling a child over a bad dream by revealing the adult to be complicit in a horrible reality. The second scene shows a woman and a man “talking shop” at a hatmakers, complaining about their employment contracts and corrupt management.

Jessica Hynes and Sophia Ally in Far Away at the Donmar Warehouse.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

But it turns out the extravagant hats they are making for a parade are to be worn by prisoners on their way to execution — whom we see ragged, beaten, and chained in a shocking tableau that “normalizes” murder as part of an artistic entertainment. The final scene reverts to Harper’s house, where during a lull from the war we see the same man (Todd) reunited with the woman he has now married whom we belatedly realize is the grown-up Joan. By this time we hear that the conflict involves not just humans but the whole natural world, with a “cloud of butterflies” having attacked Harper, cats killing babies, and deer terrorizing shopping malls — even rivers and the weather take partisan sides in this apocalyptic vision.

Far Away starts quietly but develops into a twisted fairy tale that haunts our consciousness with the hyper-reality of a nightmare. With the play’s elliptical poetry and surreal humour, the audience has to work hard to make connections between the scenes, which it transpires are set several years apart. We don’t know for sure what is going on but there are intimations of ethnic cleansing and suppression of dissidents in a totalitarian state, with the political strife ultimately descending into ecological catastrophe.

The production by Lyndsey Turner (who has directed Churchill’s Light Shining in Buckinghamshire and Top Girls at the National Theatre in the last few years) is impressively focused and direct, letting the play’s image-dense language do its work, backed by Lizzie Clachan’s flexible set which is changed for each scene within a metallic shell that descends from the flies like an alien landing craft. Jessica Hynes plays the prevaricating Harper with unnervingly calm detachment, Simon Manyonda is the discreet whistle-blower Todd who falls for Aisling Loftus’s independent spirit Joan, while on alternate performances Sophia Ally and Abbiegail Mills play Young Joan, whose childhood innocence is brutally cut short.

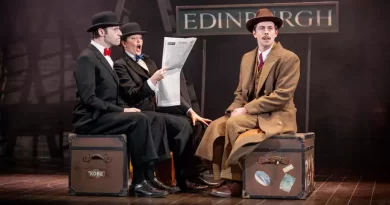

Roger Allam and Colin Morgan in A Number by Caryl Churchill at the Bridge Theatre.

Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Churchill’s A Number is a somewhat longer piece (running for about one hour) and with its more naturalistic style is also more accessible than Far Away. Again acting as a warning of where our society may be heading in the future, this time the focus is on how scientific advances — specifically human cloning — can impact on issues of personal identity in a play that examines nature versus nurture.

We start in the middle of a conversation between a widowed father (Salter) and his son (Bernard), who has just found out that he is not the only son — there are “a number” of genetic copies. Initially, Salter reassures the sensitive Bernard that he is his original son and sees an opportunity to obtain compensation from the authorities for producing clones without his permission. Later, he admits to him that he had another son first, but after the suicide of his wife and his own alcoholism, he had neglected this son, and then abandoned him by putting him into care as a young boy. Wanting to “start over,” he asked a laboratory to create another version of his son — known as B2 — whom he brought up responsibly. Hearing this revelation from his father, B2 is shocked and begins to question who he is.

Salter then has a disturbing confrontation with his estranged original son (B1) who, seething with resentment both for his abusive childhood and for being “replaced”, threatens to kill B2. Later, Salter also goes on to meet for the first time another identical son, called Michael, who turns out to be a maths teacher, happily married with three children, and not at all upset at learning he is a copy — but there seems to be no personal connection between them.

A Number looks at the emotional effects of developing technology on family relationships and how a threat to our individuality can endanger our sense of what being human is. All three sons have exactly the same DNA but because their life experiences have been different their personalities contrast. It is not explained who licensed multiple versions of the son to be produced, or why this may have been done, so the emphasis in this play is not on autocratic state control but on one-to-one relations.

Polly Findlay’s lazer-sharp production is splendidly taut, including moments of awkward comedy, with the audience close-up on three sides of the stage giving it the intimacy the play needs. Once again the design is by Lizzie Clachan, but this time her set suggests a deliberately mundane domesticity; however, the way the revolve changes our perspective of the suburban living room during the short blackouts between scenes has a similar disorientating effect to seeing three versions of one person. Roger Allam gives a superb performance as the shifty, guilt-ridden Salter who is over-concerned with money and seems to treat fatherhood as almost like a consumer choice. Colin Morgan also excels, brilliantly distinguishing the bitterly angry B1, the gentle but insecure B2, and the blandly equable Michael through body language as well as vocal expression. Once more Churchill’s beautifully precise but unsettlingly ambivalent writing shines through.