Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2018

Jeremy Malies in Midlothian

30 August 2018

My twelfth trip to Edinburgh for this magazine and the schedule is as tight as a battle plan; invasions have been based on looser logistics. Any veteran will tell you that one’s time at Edinburgh is divided into slots of an hour with intricate strategies for avoiding the crowds as you jostle between venues.

A roving commission and freedom to explore work at small venues means I should remain in touch with the original utopian ideals of the Fringe as an alternative to mainstream festivals and can avoid elements that journalist-turned-producer Lynne Parker has wryly dismissed with: “It’s not really a Fringe festival any more – it’s a corporate trade show, a festival of fake grass and turf wars between beer brands.”

You can still find small youth companies such as Close Up Theatre from a school in Cheltenham willing to enter the increasingly competitive fray. As in previous years, the group has brought its version of 1984 to the city. I just hope that the young performers are following developments under Kim Jong-un. Orwell finished the novel in 1949, the year that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was formed. Occasionally I wonder if the text was sent to the founders of the country and somebody said: “Do you think you could use this as a blueprint?” Director Rebecca Vines flings her Winston Smith (Orlando Giannini) into Room 101 using minimal props, knowing that ensemble work has already made the dystopian superstate more than usually chilling. The piece is at Greenside in Nicolson Square, at other times a Methodist church but on this occasion the setting for the most godless of societies.

Titus Andronicus by ExADUS Theatre Company at the inappropriately named venue of Paradise in the Vault is, amid a competitive field, one of the most gory versions I can remember with projectile vomiting and some spectacular dismemberment. Why are young companies so attracted to a play with scarcely a good or redeeming figure in it? Still, the quality of verse-speaking by actors with little experience is first-rate. As usual, the opportunities for people-watching are superb and I marvel as I observe a couple of blue-rinsed American matrons pattering into this show, each clutching enormous gin and tonics. They are certainly ensuring that their trip to Edinburgh touches all bases.

Owain Gwynn and Daniel Llewellyn-Williams in Not About Heroes.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Underground Railroad Game at the Traverse Theatre uses memories of a crass schoolroom exercise experienced by one of the performers as the springboard for a critique of simplified condescending versions of US history. As a middle school pupil in Pennsylvania, Scott R. Sheppard was asked along with his classmates to play a game in which they ferried black ragdolls across an imagined Mason-Dixon Line to Canada or Union states. Even as a child, Sheppard was disturbed that the only black bodies in the room were effigies, and he had wisdom beyond his years to question just exactly what kind of school game would divide children into halves with some of them playing the role of slave-owning Confederates.

Sheppard and his associate, Jennifer Kidwell, are Ecole Jacques Lecoq-trained and while it infuses their approach, they wear the method lightly. The show involves much audience interaction, moving from the school lesson beginning to assess received historical perspectives even if they are nominally liberal and ‘safe’ narratives. The show transferred immediately to the Soho Theatre, London.

It’s a tenet of Trump-Lear at the Pleasance Courtyard that the most maverick president yet is subverting culture, even the culture that seeks to satirize him. Forget Alec Baldwin’s laboured Trump routines, impersonator David Carl nails the voice and mannerisms while showing that a Trump cabinet meeting can resemble the opening of King Lear where the map is divided or the later stroll on the heath with Fool and Gloucester. He might be on record as saying the more orange makeup the better, but there is much subtlety (and a surprizing amount of undiluted Shakespeare) in David Carl’s one-man show. The president has two daughters (Ivanka and Tiffany) and while Ivanka is showing the strain and her role has always been foggy, she still has an office in the West Wing. Neither of the daughters has betrayed him. Carl brings in mannequins of previous American presidents who he can of course dismiss as puppets. There is no Deep State here and however deranged he may be, nobody is pulling POTUS’s strings.

Last year I was transported by a mime show, Translunar Paradise, from the company Ad Infinitum. Their piece this year, No Kids is high on my priorities. It’s a discussion of issues surrounding gay parenting in which joint artistic directors Nir Paldi and George Mann, a real-life gay couple, play a blend of themselves and a fictionalized pairing. The play sees them debate the issue of having children as a gay couple. How significant is prejudice against or even bullying of a child with same-sex parents likely to be? What criticism might the parents face from other adults? The discussion is never narrow or self-absorbed, and the writers make the point that on a planet with inadequate resources, couples of any gender should think hard about parenting.

The usual acting question of “What’s my motivation?” has an extra dimension here. By wanting to have children, are a gay couple being railroaded into heteronormative goals? The pair dance to songs by Madonna – hardly my favourite. Sir Elton John and his partner David Furnish have a son born to a surrogate mother. Music solely by Sir Elton? Now that would have been more apposite and more to my own taste. The play has many spirited exchanges but the opinions are often just that, positions on social and parenting issues that could be voiced just as effectively in a non-theatrical form.

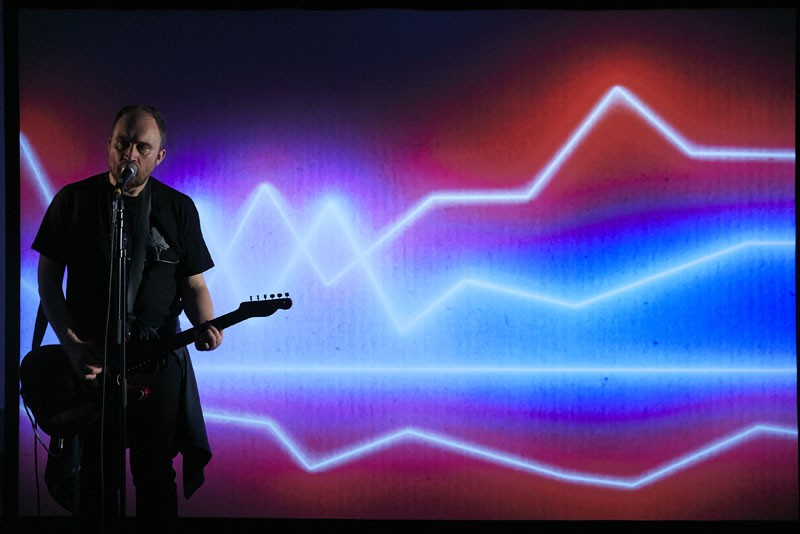

Chris Thorpe in Status.

Photo credit: The Other Richard.

Generally, I noticed less enterprise in terms of location with few companies creating site-specific projects or using found space. A pleasing exception was Power Plays, a series of four pieces in an apartment with a focus on gender equality and women in theatre. Unless I missed a lot in this genre, verbatim theatre using documents, recorded minutes, witness testimony and speeches from real events has also fallen out of fashion. It’s a modish well that young directors in a hurry may have dipped into once too often but the form has always appealed to me. The half hour I spend distributing flyers for a friend of a friend is profoundly depressing. Few people will take them (there may of course be something wrong with my technique) and festival-goers now want to save the planet and expect you to be more savvy by using social media.

I return home having ignored every lesson absorbed from previous festivals, indiscipline that now prompts me to list the Plays International & Europe guidelines for staying sane in Edinburgh. Go to a maximum of four pieces a day. Engage with performers hawking their shows but run a mile from any young person who so much as mentions Stanislavski or claims to have ‘reworked’ Shakespeare. And Bogart’s pronouncement in The Maltese Falcon holds true for theatre publicists; the cheaper the salesman the gaudier the patter so beware of promoters talking loudly in lounges about how well their show is doing. Combining theatre-going with people watching underlines one lesson: David Mamet’s maxim holds true for interaction between performers, agents and venues in the competitive environment that is Edinburgh. Everything can be analyzed in terms of “Who wants what from whom and what happens when you get there?”

Scott R Sheppard and Jennifer Kidwell in Underground Railroad Game.

Photo credit: Ben Arons.