“Arcadia” at the Old Vic

David Wootton on the South Bank

★★★★☆

9 February 2026

Even before a performance of Tom Stoppard’s masterly Arcadia begins at the Old Vic, its elegant set, designed by Alex Eales, announces that it is to be a play of ideas. Not only is Carrie Cracknell’s assured production presented “in the round”, with the audience on all sides, but the stage is also circular and able to revolve, and is inlaid with a plan of Sir Isaac Newton’s classical universe. Above this relatively solid ground hangs a dazzling kinetic sculpture, combining ellipses and orbs, which is suggestive of the exhilarating instability of post-Newtonian physics. Sparks are clearly going to fly.

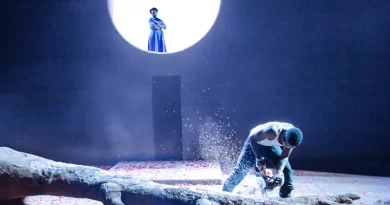

Isis Hainsworth as Thomasina.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Simply furnished with a table and chairs and a quartet of curved benches, the stage itself represents the school room at Sidley Park, a country house in Derbyshire. The action opens in 1809, but the gradually shortening scenes alternate between the early 19th century and the late 20th century until the point at which those periods directly parallel each other, and then even overlap, in a deeply affecting way. (Suzanne Cave’s stripped-back costumes helpfully define the two ages.)

Thomasina Coverley, the highly intelligent 16-year-old daughter of Lord and Lady Croom, has been set to solve Fermat’s Last Theorem by her tutor, Septimus Hodge. However, she is distracted from her task by the desire to know the meaning of the phrase “carnal embrace”, which she has overheard. The stimulating sparring that develops between them, as he tries to keep her on task and she demands the truth, reveals both their individual qualities and their strong mutual sympathy, especially as played by Seamus Dillane and Isis Hainsworth.

Apparently inspired by the pioneering mathematician Ada Lovelace, the daughter of Lord Byron, Thomasina is so astoundingly curious and intellectually advanced that she proposes a means of writing “the formula for all the future”. And, though she is unable to publish this idea herself, it proves influential by filtering through the play and across time to be taken up by the modern characters. While such theories are sophisticated, she shares them as a teenager in immediate and accessible imagery, and so, for instance, explains the inevitability of entropy by alluding to the stirring of jam into her favourite dish of rice pudding.

Seamus Dillane and Isis Hainsworth.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Septimus interprets such stirring in a positive way, associating it with “free will or self-determination”. His free will, and its fallibility, is then exposed with the entry of the poetaster, Ezra Chater (an amusing Matthew Steer), who accuses Septimus of seducing his wife in the “carnal embrace” that had piqued Thomasina’s interest. Septimus admits his action, but so flatters Chater by praising his poetry that Chater thinks that his wife has loyally seduced Septimus to ensure that he writes a positive review of his new volume, The Couch of Eros. As a result, the threat of a duel is allayed.

The conceptual geography of human agency and its often disorderly outcomes is manifested in the person of Richard Noakes (played by Gabriel Akuwudike), a landscape gardener who has been employed by Lord Croom to remodel the grounds in the latest Gothic or Picturesque style. When Lady Croom’s brother, Captain Bryce (a suitably haughty Colin Mace), complains that his plan “is all irregular”, Noakes takes this as a fitting compliment. Lady Croom herself is even more distraught at the loss of the seemingly natural grounds that had conformed to the Beautiful style favoured by Capability Brown. “Et in Arcadia ego”, she quotes in Latin, so emphasizing that the play’s title alludes to a Classical vision of an idealized, well-ordered past.

Lady Croom is a dominating matriarch, and appears even more so as her husband remains offstage. Stoppard allows her several sub-Wildean witticisms that clearly relate her to Lady Bracknell, and this likeness was made the most of by Harriet Walter, who played the role in the original production of the play, at the National Theatre in 1993. However, at the Old Vic, Fiona Button presents the character as softer, subtler, and more sympathetic, so that it is more understandable that Septimus should be attracted to her.

Stoppard paints such a delightfully detailed picture of Regency life that it feels almost sufficient in itself. Nevertheless, he then provides perspective on the preoccupations of 1809 through the investigations of two modern writers on Romanticism. Hannah Jarvis is the author of a best-seller on Byron’s mistress, Lady Caroline Lamb, who is now researching the mysterious hermit of Sidley Park. Bernard Nightingale is a university academic who wants to interest Hannah in his theory that Byron stayed at the house. Unfortunately, Bernard has written an extremely negative review of Hannah’s book, so that any attempted collaboration proves combative.

Their disagreements are strongly and entertainingly portrayed by Leila Farzad and Prasanna Puwanarajah, though their relationship lacks perhaps the last degree of complex antagonistic chemistry, which made Felicity Kendal and Bill Nighy such a joy to behold back in 1993.

Hannah and Bernard are the guests of the latest generation of the Coverley family, represented on stage by their teenage children in three impressive, convincing performances by actors early in their careers. Both Valentine (Angus Cooper) and Gus (William Lawlor) are in love with Hannah, while Chloë (Holly Godliman) is attracted to Bernard.

A graduate student of mathematics, Valentine is studying the estate’s game books to understand how the changing population of grouse follows a formula of iterated algorithm, which has only been in use for two decades. He then discovers in a primer that his forebear, Thomasina, was working on such algorithms almost two centuries earlier, and also understood the concept of entropy.

The game books reveal that Bernard was correct in his assumption that Byron had stayed at Sidley Park, while other evidence confirms Hannah’s belief that it is Septimus who became a hermit (after Thomasina died in a fire). However, Bernard is so certain that Byron killed Chater in a duel that he makes a precipitous public statement. With the aid of a reference in Lady Croom’s garden book, Hannah proves that Chater lived to become a botanist and died from a monkey bite while on an expedition to Martinique, and she writes a letter to The Times to make the fact known.

The separate time frames are initially and subtly integrated by young Gus who, having stopped speaking at the age of five, silently haunts the stage, putting down objects, such as an apple, which are then used by the early nineteenth-century characters. Furthermore, Gus is parallelled by Thomasina’s talkative brother, Augustus, who is also played by Lawlor. Then the modern teenagers don Regency costume for a fancy-dress party. Finally, Septimus and Thomasina in 1809, and Hannah and Gus in 1993, waltz together (to music composed by Stuart Earl). In a work that relies so much on quickfire dialogue, it is a magical and moving moment, confirming that the entire drama comprises a dance to the music of time.