Adelaide Festival 2019: Malcolm Page

Malcolm Page at the Adelaide Festival

1 March 2019

The plethora of arts festivals around the world are still loosely modelled on what Edinburgh Festival has been doing for 72 years. Theatre, opera, orchestra, and dance come together – often from overseas which makes them special. The programming, heavily shaped by the tastes of the artistic director, is usually unashamedly highbrow. Adelaide, the oldest and biggest of Australia’s festivals, took place, as it does annually, in March, and was accompanied by a Writers’ Week outdoors under shady trees, and an enormous Fringe. Adelaide’s events — unlike Edinburgh’s which are in the city core — were far apart with two productions at the showground and two in the suburb of Norwood, making it difficult for a newcomer to take in everything.

The main festival had twelve music, four dance, and three ‘family’ events, plus an opera, one musical, two popular physical theatre shows, and ten theatre performances. Six of the theatre pieces are Australian exclusives. It seems regrettable to me to have brought in a show from Europe and then not to have it seen in other neighbouring cities. While the Edinburgh international programme is usually all heavyweight, the Adelaide shows divided into four or five that were truly big. All the others had more of a Fringe feeling, meaning a small cast on a bare stage.

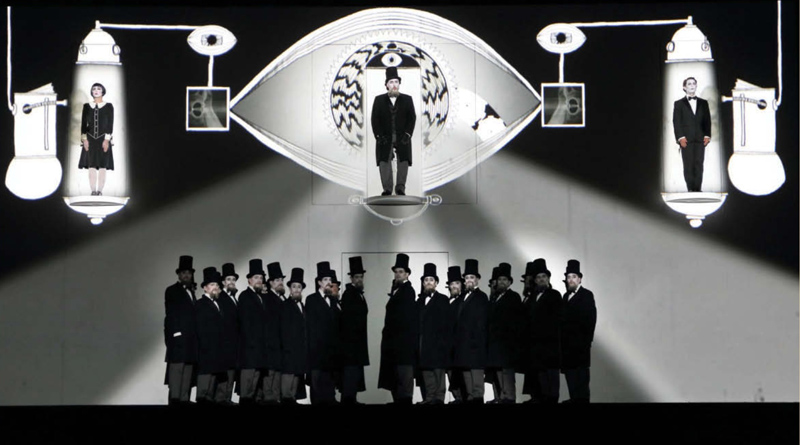

The Magic Flute by Komische Oper Berlin.

Photo credit: Tony Lewis.

The top event was Mozart’s The Magic Flute, brought in by Berlin’s Komische Oper and re-worked by Barrie Kosky, Suzanne Andrade, and Paul Barritt. The opera becomes an animated film, the performers isolated on platforms and reduced to two-dimensional figures. This is all about film and exploring the possibilities of animation. The images are frequently surprising and sometimes abstract with the uses of lines and colour, at times illuminating the music. A dimension includes mostly obscure imagery from 1920s cartoons like Felix the Cat and Betty Boop, as well as the silent films of Weimar Germany (those made, for instance, by F. W. Murnau).

The animation diminishes the human; here, technology is more important. This entertainment is surely a curiosity and will not tempt any other opera into bringing animation on a screen onto their main stage. This particular Magic Flute, which premiered in Berlin in 2012, has been seen by half a million people in 25 cities. Perhaps audience members who do not attend operas are attracted by this approach – meant to be fun, with the singers mattering too little.

Counting and Cracking is a three-and-a-half-hour epic about the experiences of four generations of Sri Lankans in Australia and in Sri Lanka between 1957 and 2004.The first half of the play is focused on mainly domestic matters, and then matters becomes profoundly political as it focuses on the Tamil/Sinhalese conflict and the shift from democracy to tyranny. Politics inevitably seriously impacts and may become a matter of life and death. We meet a war profiteer, an air conditioner installer, a woman mathematician, and many more in a cast of 16 of five nationalities. Scenes are not chronological. The director Eamon Flack comments: “I realised early on this was an Australian story that didn’t look like what we thought an Australian story looked like, but it was”.

I admired so much about Counting and Cracking the music trio, the colourful saris, the occasional humour (mending a computer; swimming shown by sliding down a long wet blue cloth). The drama communicates Sri Lanka’s troubled history while raising wider questions about any migrant experiences and the issue of dual nationality. Closing allusions to Amnesty International’s reports on human rights in Sri Lanka and the way Australian now excludes any Asian “asylum seekers” who arrive by boat moves us from detachment back to the realities of our world. Manus discussed below, later in the week returned to this important issue.

The Magic Flute by Komische Oper Berlin.

Photo credit: Tony Lewis.

Blaas is on a much smaller scale. Blaas is a Dutch word meaning “blow, breath, bubble, and bladder”. The Dutch mime Schweigman& presented Blaas, which opened at the Oriel, Netherlands Festival in 2013 and also played at the Fadjr International Theatre Festival in Tehran in 2018. Although there are no words in Blaas, sometimes we hear music or other sounds. For half an hour we watched a huge white hollow cube go backwards and forwards across the stage, changing shape and eventually assaulting the audience. This part is slow, I had to struggle to try and achieve a sublime understanding of the “non-rational intuitive perspectives” promised in the leaflet.

The audience becomes even more directly involved in the second part as we crawl up a tube (back to the womb, or out of it) into a grassy space enclosed by white fabric to eventually be released through another long, long tube which emerges far from the theatre. It was one of those experiences that everyone perceives differently.

Next was Manus, a play meaningful for Australians. Manus is one of the two small islands off the country’s north coast to which “asylum-seekers” (the term “refugee” is avoided) are confined year after year in camps (seen as prisons or concentration camps). This harsh treatment is I suppose meant to be a deterrent to others, yet it is outrageous. This play is a protest and could not be more explicitly critical. The language used in the play is Persian, subtitled and verbatim. lt is an assemblage of interviews with people, mostly Iranian, who have been confined to Manus. lt is difficult to write about as theatre. There were five men and three women; the sets were made by moving red petrol cans about, and this movement provided the main visual.

Counting and Cracking.

Photo credit: Brett Boardman.

The Festival’s top events included Mozart‘s Requiem elaborately staged by Romeo Castellucci (discussed by my fellow correspondent Ben Brooker on this website) and Aleppo; A Portrait of Absence. Here ten actors told verbatim stories about life in war-torn Aleppo to audience members one-on-one. “The art of telling, the necessity of listening, is everything”; says the publicity. Storytelling, whether fact or fiction, is a response to the horror of war.

The Adelaide Fringe is the second largest in the world; of course, Edinburgh is first. Heavily weighted with comedians, the programme lists one hundred and forty-six performances under “Theatre”. Nearly all of these are new and locally created or on a world fringe circuit. Moliere’s Tartuffe, Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter, and a seventy-minute The Tempest are among very few using existing scripts. Medea and Orpheus and Eurydice draw on Greek myth, and there’s a version of a Kafka story. The high figure is somewhat misleading, as many are present for only one or two of the four weeks. So if you attend the Adelaide Festival, before being excited by a description, check when the play is on and if it is at an accessible location. That there were thirty-nine “circus and physical theatre” performances struck me as surprisingly high, given that “magic” and “cabaret” have listings too.

The heart of the Fringe is located at Gluttony and Garden of Earthly Delights. These adjoining sites take over a large chunk of parks and each has some dozen theatre spaces, with a different show every two hours in each – all day at weekends and in the evenings on weekdays. Both have many places for eating and drinking and both drew big crowds when l was there. Holden Street Theatres, a bus ride from the city centre, gathers some of the more serious and ambitious plays.

I commend two shows which had appeared at Edinburgh Fringe. Tartuffe, adapted by Liz Lochhead, is set in Scotland in the 1940s and is cut to under an hour and to four characters. lt is in rhyming verse and assertively in Scots (English subtitles are provided, perhaps unnecessarily). The tone is relentlessly broad and farcical. I laughed a lot, even while missing complexities of characterization.

Lecoq-trained actors Jonathan Tilley and Jess Clough-MacRae perform Attenborough and his Animals, which they devised. The bulk of the script is verbatim David Attenborough taken from his many nature TV programmes. Tilley has the voice to perfection: reverential, amazed, breathy, observations ending unexpectedly, pauses in mid-sentence; slightly extended, these traits become comic. Equally impressive, Clough-MacRae plays everything from a crab to a whale, at her best perhaps as a baby seagull clamouring to be fed. She physicalizes each animal with a huge range of sounds. I am astonished by how well they sustained their show for an hour. Though very amusing, Attenborough and his Animals adds to our respect for the wonders of the animal world.

The first phase of Manus is about the dangers of crossing from Indonesia in a small boat. In the island camp there is little hope of the current confinement ever ending, as Australia ruthlessly enforces its water borders. The final phase of the play shows hostility from locals that includes a killing and stoppage of food and water.

Nazanin Sahamizadeh the “deviser” comments, “What we hear and see is not only stories of some refugees who are strangers to us … during the play, they are someone’s mother, wife, beloved. Their fate becomes more important to us.” The show previously played only in Teheran and at festivals in lndia and Bangladesh. A leaflet distributed outside declares:”$1.15 bn was spent by the Australian government on offshore detention in 2018 and 201 9.” Why? Of all the shows l saw this was the only one that was not packed. Palmyra played at the same theatre a few days earlier. The title is irritating in that Palmyra, the famous Syrian ruins partly destroyed by ISIS a few years ago, are never mentioned. A bare stage, two chairs, two men talking, with long pauses, inconsequentially. Tedium. l should credit the actors: Frenchman Bertrand Lesca and Nasi Voutsas, a Londoner of Greek descent; they have worked together for four years.

The business is around broken crockery: first a broken plate, then one smashed after being dropped from the top of a ladder, then many boxes worth of broken china were scattered across the stage. Can a woman in the audience be trusted with a hammer? A random and perhaps improvised talk of Paris and French poets. Tensions and then hostility between the two men. For some moments l was uncomfortable, even chilled. Finally, one man exits – and we watch – for a long time – as the one remaining sweeps up broken china. Did I miss something? Voutsas tells us, “What we‘re talking about is universal human feelings and emotions like revenge, aggression, and violence. The show is quite allegorical.” Does the allegory fail, or is it my failure to respond? [Editor’s note: Palmyra was reviewed by another PIE correspondent at the Brighton Festival in 2018. He was similarly underwhelmed].