“Local Hero” by David Greig and Mark Knopfler: Minerva Theatre, Chichester

Simon Jenner in west Sussex

18th October 2022

Happer, the comet-gazing CEO of Knox Oil (played by Jay Villiers) sends executive employee Mac (Gabriel Ebert) from Houston to the village of Ferness: to buy it. Local Hero might be based on Bill Forsyth’s offbeat 1983 film – successor to equally offbeat gem Gregory’s Girl – with the music and lyrics still by Mark Knopfler once of Dire Straits, who’s present in this production; but it’s David Greig writing the book. Directed by Daniel Evans, Chichester’s Minerva Theatre mounts one of the most enchanting musicals you’ll see for a long time.

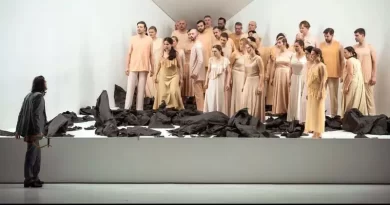

The company with Rodney Earl Clarke in foreground.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Greig’s someone whose characters can echo the selkies (seal people) of myth, and there’s more than a tang of his small masterpiece Outlying Islands of 2002 with its triangular relationship, by the time this ends; with subtle twists to the original. Like Mac in a phone box at the end of Act One, you expect change.

Frankie Bradshaw’s set delivers its brio at the start. A metallic stage-sized walkway curls up and slightly back on itself, a platinum wave: so the whole Houston-clad ensemble dance with brick phones to ‘A Barrel of Oil’ as a Dow index created by Ash J Woodward slithers down and across the whole floor.

Mac, whose family are Hungarian not Scottish as he protests, has been yanked from obscurity (“Houston, We Have a Problem”). Moments later gas-jets flare left and right then dry ice with a scudding underfoot of clouds, accompany the hoisting of a reluctant Mac in a Pan Am cabin chair, all lit seamlessly by Paule Constable with Ryan Day. Not long after this the front rostra is lifted off to reveal sand, a comfy old chair appears magically stage-right, a telephone box and hotel bar chunter on and off, and with the exception of a little stage business, the superb set stabilizes into the business of storytelling.

The ensemble now settle into character; each recognizable. It’s a beautifully tailored world, as “Welcome to Ferness” manages to introduce them: Ali Craig’s Ownie as Gordon’s hard-up local client, Murray Fraser’s canny hard-drinking Iain, Julie Cullen’s Pauline with a yearning to get out, alongside big-blonde-Eighties-hair Rhona (Rachael Kendall Brown in wondrously acidic voice); Rodney Earl Clarke’s Reverend Murdo convening community speculation with baritonal authority, then reverting to ‘Amens’ every time Mac saunters past. The infectious “We’re Going to Make a Killing” mixes exuberant Eighties greed with genuine aspiration and more than a touch of transatlantic revenge-engineering. ‘That’d Do Me’ though is a more sympathetic number, impossible not to identify with in its lilt, now almost nostalgic.

Gabriel Ebert and Rachael Kendall Brown.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Mac swiftly strikes up rapport with local Gordon (Paul Higgins), hotel proprietor who like everyone else multitasks and Mac finds himself meeting the accountant and chief negotiator – Gordon – in his office with a bell setting the fee running, as we’ve seen locally. Cue some haggling, the arrival finally of Viktor (the excellent Joshua Manning) Soviet Russian trawler captain with capital investments to nurture with Gordon, and a shortwave radio love interest in Jackie Morrison’s Mistress Fraser, who leads “I Wonder If Can Go Home Again” and is one of this show’s draws. Mac discovers a formidable oil-savvy team.

That’s nothing to the team that opposes them all, as Hilton McRae’s twinkling laird Ben teams with Gordon’s freewheeling Glaswegian ‘blow-in’ Stella (Lillie Flynn). Moonlighting to Edinburgh and back for a reason, they’re up against the village, now offered millions. Stella’s in love with the island as well as Gordon’s dancing skills. By contrast people living there endure decades of their children leaving.

That’s the subtlety of this piece. Mac falls for Gordon’s lifestyle, and vice versa in a bromance (“In an Ideal World”) just as he falls for Stella – despite her reluctance. That’s where the triangle of Outlying Islands comes in, with two Cambridge ornithologists meeting local sassy teenager Ellen in 1939 who makes an unusual set of choices with a backdrop of germ-warfare-testing. Stella becomes very much a Greig character: interventionist, romantic, but wiser than others in her realism.

Flynn’s solo “Rocks and Water” is both plangent lament and prophesy, with the underlying question expounded in the programme notes: despite deprivation overcome in a spectacular enrichment of the whole area – based on real events – are people happier? Flynn’s the affecting heart of this musical, quietly mesmerizing.

We see McRae’s unique qualities here too: quietly mischievous, playfully wise. Some might have caught his Sir Henry Harcourt-Reilly in the 2015 Coronet revival of T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party. Though darkly subtle mischief is what McRae does better than anyone, even in his recent performance in Strindberg’s The Dance of Death. He enjoys a solo “What A Life” introducing him, and with Flynn draws the narrative to fable. In “Cheerio Away Ye Go”, there are antagonistic lines drawn in the sand: it’s a boppy banishment of billions as Stella hurls syncopated defiance.

Paul-Higgins, Rachael Kendall Brown and Ali Craig.

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Ebert comes into his own particularly in Act Two, with Flynn in “Numbers” where they disagree between numbers-based and experiential views of life (you can see where this adds up) and his bromance with Higgins’ Gordon. He then flowers in solitude with taking up Fraser’s “I Wonder If I Can Go Home again” and reprising his Houston song, undergoing sea changes of identity. His voice blossoms too; we begin to invest in Mac, where before he was a nodal point who began to shift. Ultimately he’s siding with very different people. But there’s always a deus ex machina – literally, a god out of a chopper – to resolve things.

Higgins is thoroughly believable as Gordon, leading the company in “Filthy Dirty Rich”, partnering Ebert in “In an Ideal World”, which doesn’t quite hint at Higgins’ dominant role as leader of the community. His personable, shrewd, flexible character is one who would like Mac’s car and job. Higgins – and Greig – make this topsy-turvy appealing rather than venal, showing its flaws as contingent on the alternative.

The plot’s unravelling is its even-handedness. With Happer’s original being the film’s expensive Burt Lancaster, there’s a benign billionaire storyline, one obsessed with numbers – again – and comets. Now there’s a plot; Villiers enjoys his transformation.

There’s fine work from Liz Ewing’s laconic hip-flasked Netta, trundling a baby whose identity – well, go and find out. Betty Valencia’s cavorting, energized Shona and Craig Hunter’s quietly wild Lachie. Sasha Milavic Davies contains all this movement on the Minerva floor, where several parties lurch on the night and rise with paracetamol-inducing sluggishness on the morrow. Indeed, in “Never Felt Better” Milavic Davies choreographs a definitive hangover-shuffle, with people emerging from sleeping bags in slow beach reveals in the manner of Trinculo and Stefano. And there’s more than a touch of Prospero in Ben, underscoring a Tempest-like feel and theme of what to resolve with rough magic.

The band led by Richard John are one great draw. Indeed, actors pop up next to them in disembodied Pan Am captains or Fraser as a radio voice. The ovation for them after the instrumental finale “Going Home” follows a standing one; not a routine event in the Minerva. Paul Arditti makes the sound envelope punchy, not overwhelming – and I was next to the band, never missing a word of the chorus.

This enchants. It plays for a month longer and I urge you to see it. It should endure just because it’s not a conventional musical; the music weathers beautifully into Greig’s subtly different storytelling. It’s timeless, and like the comets at the heart of its plot, it should go on reappearing with the same bright magnitude.