“Girls & Boys”, Royal Court Theatre

Neil Dowden in Kensington and Chelsea

17 February 2018

Dennis Kelly may have had a lot of popular success writing the books for family musicals Matilda and Pinocchio, but in his plays violence usually rears its head. His new work Girls & Boys, a 90-minute monologue performed by Carey Mulligan, is no exception even if the full horror is not revealed until the end. But when it does come the impact is gut-wrenching.

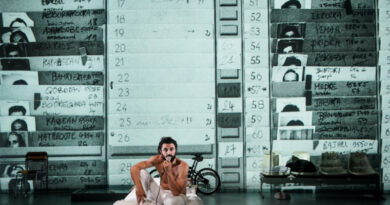

Carey Mulligan.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

Mulligan plays the role of an unnamed woman who alternates between addressing the audience directly to narrate the history of her relationship with her husband (who is also unnamed) and the story of her unexpectedly blossoming career and interacting with her own young children Leeanne and Danny who are never seen on stage. The mood at the start is upbeat and comical as she outlines a whirlwind romance with the man who became her husband, followed by a full family life juggled by both parents doing busy jobs, but the tone progressively darkens. There is a strong hint fairly early on that we are heading for a tragic denouement.

The woman’s memorable opening line is, “l met my husband in the queue to board an easyJet flight and l have to say l took an instant dislike to the man.” She describes how, after initially finding him irritating while waiting for a plane at Naples airport, she falls for him when he puts two gate-crashing female models in their place with devastating dry wit. Having been through a “drinky, drunky, laggy phase” she is now ready to settle down, and their passionate love develops quickly into home life with a daughter and son.

Both husband and wife are from working-class backgrounds and are hungry for success. He has already established a thriving business importing antique wardrobes from the continent, and she manages to con her way into the film industry as a personal assistant to a producer. She rises rapidly; with her husband’s encouragement, she goes on to co-found a company making socially relevant documentaries which are nominated for awards. But everything starts to unravel when, after shifts in the market, the bottom falls out of the husband’s business and it goes into bankruptcy.

Carey Mulligan.

Photo credit: Marc Brenner.

He becomes depressed and angry. He is behaving so strangely towards her that she thinks he is having an affair. lt turns out he thinks she should have given him more emotional support, and he can’t stand her doing so much better than him in her career. She in turn is bitterly disappointed: “l had thought that the man I loved had changed. But this was so much worse. This was realizing that he had never existed in the first place.” But it gets far worse than professional jealousy when she insists on divorce. After they have separated, her ex-husband gains entry into her new flat and murders their two children.

Kelly’s play is a feminist drama dealing with toxic masculinity. It implies that testosterone has a habit of spiralling out of control; that men have violent impulses built into their DNA. Indeed, after the devastating climax, we see the woman’s address as more like an educational talk to an invited group on the dangers of male violence than the confessional life story to a confidante that her conversational style suggests. The fact that both the woman and the man are unnamed suggests that their relationship is archetypal.

This sharp female/male divide is reflected elsewhere. The woman has to force her way through a patriarchal (as well as class) barrier in her career. Even the 73-year-old male academic who has devised a system to make it more difficult for men to abuse power tries to “cop off” with her and her teenage female assistant while they are making a documentary about him. The two children are also gender-stereotyped in the ways they play. Whereas Leanne is constructive and creative (wanting to build skyscrapers out of mud), the younger Danny just wants to smash things up in his war-like games.

This all seems a bit schematic and reductive, as if people are prisoners of their biology. Of course, in terms of domestic violence (and violence in general) men dominate the statistics, but this play does appear weighted against the male of the species. Perhaps that’s inevitable given that it is a monologue by a woman who has suffered appallingly at the hands of a man, so we are confined to a single point of view. The trouble is we don’t get to know the husband very well, so his dramatic personality change leading to his extreme violence comes out of the blue.

Screen-star Mulligan, who has made an impressive if limited number of stage appearances, returns to the very theatre where she gave her professional debut 14 years ago to deliver a brilliantly assured performance as a survivor of a terrible tragedy with great technical and emotional range — it’s a tour de force to hold the audience alone so well for so long. With her blonde hair pulled back, wearing an orange shirt and dark-reddish trousers, she cuts a rather androgynous figure, her estuary accent and ballsy vernacular projecting someone who is determined to move upwards.

Early on, it is her streetwise cheek that engages as she entertains us with messy stories of youthful escapades and non-conformist views. Like a top stand-up comedian, her pay-off lines are perfectly timed. And her concerned if sometimes frustrated scenes at home looking after her lively, invisible children are enacted with persuasive physicality and are amusingly believable; so when she suddenly tells us, “l mean it’s not like they’re actually here … I know they’re dead”, a sudden chill descends – it is not a theatrical device but a wish-fulfilment based on love. This is a convincing portrait of a gutsy woman who refuses to be just a victim and is determined not to give up on life even when life has given up on her.

Lyndsey Turner directs with sensitivity and restraint. In Es Devlin’s eerie design, a sky-blue box contains Mulligan in her direct addresses, while in her domestic interactions the kitchen/living room is bleached out to a ghostly ice-blue colour, with the odd toy highlighted in bright reds and oranges – as if vitality has been drained out of the home with only a few memories still alive.