“Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” at Hartford Stage

Robert Schneider in Connecticut

5 November 2024

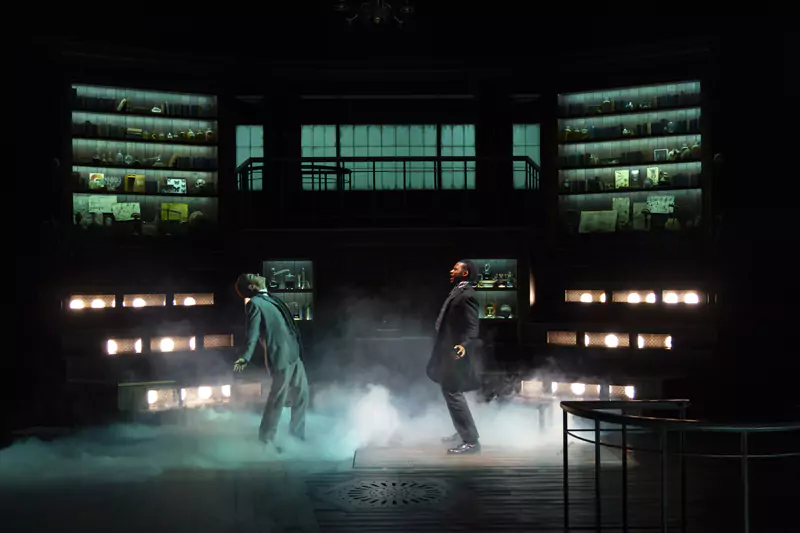

The new production of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at Hartford Stage has a lot going for it: exquisitely tailored Victorian costumes by An-lin Dauber, a rich and resourceful set, riddled with secret compartments by Sara Brown lit in dark, moody gorgeousness by Evan C. Anderson; carefully-paced and shadowed direction from Melia Bensussen and good performances all around. What distinguishes it from many previous stage versions of Robert Louis Stevenson’s turgid novella is ideas. Adaptor Jeffrey Hatcher read Stevenson deeply and found ways to make Dr. Jekyll’s inner torment, largely recounted in letters and journals, highly theatrical.

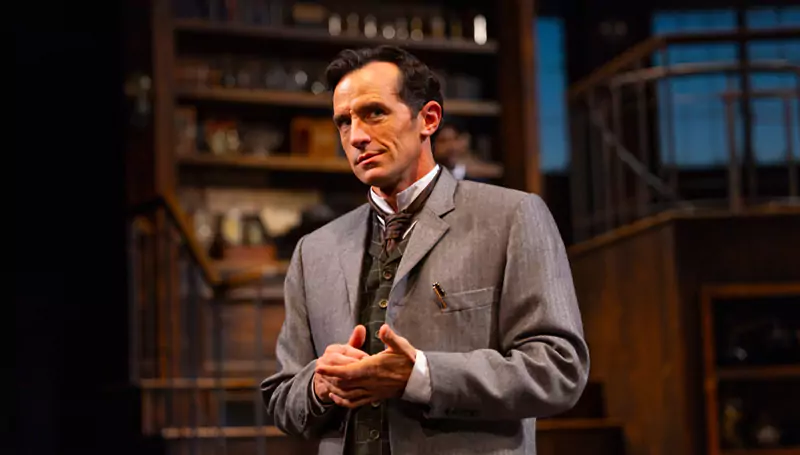

Nathan Darrow and Nayib Felix.

Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson.

The first idea, expounded by Nabokov, among others, is that Jekyll doesn’t represent good and Hyde evil. This is no cheap melodrama; people are compounded of different elements. Notwithstanding this, Dr. Jekyll (Nathan Darrow, younger and slimmer than Stevenson’s description) would like to be better than he is. He wants to spin off his evil tendencies as a separate personality. This would allow the jovial Jekyll to continue his moral ascendancy unburdened by the turpitude of his faults and unbothered by the memory of his youthful indiscretions.

Those faults and indiscretions are numerous: he’s proud, more than a bit arrogant, he has little patience for colleagues who don’t meet his high standards. In fact, there’s more than enough evil in Henry Jekyll to spawn several alter egos—and this is the biggest of Hatcher’s ideas. There isn’t one Hyde at Hartford Stage but several. Actors in the ensemble can drop the character they’re playing and suddenly turn into a Hyde. Potential Hydes are everywhere: his rival at the institute, Dr Lanyon (Nayib Felix); his friend, Dr Utterson (Omar Robinson); his solicitor, Sir Danvers Carew (Peter Stray), even his faithful butler, Poole (Jennifer Rae Bareilles). As he gradually loses control of the transformations, the shifts become sudden and unpredictable. At one point or another, almost everybody in Jekyll’s entourage becomes a Hyde.

Stevenson’s Jekyll makes no bones about the pleasure of Hyding:

“There was something strange in my sensations, something indescribably new and, from its very novelty, incredibly sweet. I felt younger, lighter, happier in body; within I was conscious of a heady recklessness, a current of disordered sensual images running like a millrace in my fancy, a solution of the bonds of obligation, an unknown but not an innocent freedom of the soul. I knew myself, at the first breath of this new life, to be more wicked, tenfold more wicked, sold a slave to my original evil; and the thought, in that moment, braced and delighted me like wine.”

Hatcher’s final good idea is to point out that evil is not only thrilling, it’s positively sexy. Instead of giving Jekyll a panicked fiancée as previous adaptors have, he gives Hyde a girlfriend, Elizabeth Jelkes (the affecting Sarah Chalfie in only her fourth professional role). Jelkes finds Hyde irresistible even though she knows how bad he is. Jekyll wants her and tries to save her, but she only wants Hyde.

Stevenson’s novella is the child of Victorian repression, but it still speaks to us today, even writ large in our politics. Anytime opposing forces battle for ascendency in a human soul, anytime the gap grows too large between the smooth exterior and the rocks and crags of the inner being, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde will be worth reading. In Jeffrey Hatcher’s adaptation it’s certainly worth playing.